Rebelling Against the Status Quo With Art and Anger

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

Throughout the 1960s, Los Angeles, Hollywood underwent drastic transformation from its previous existence. A “Second Great Migration” took place in the 1940s resulting in an influx of African-Americans from the South in the North, West, and Midwest, changing the culture of L.A. and its outskirts. Black women continued to grace the screens of Hollywood films through the 1960s but producing their own content through a Hollywood studio still remained a rarity. The women who starred in major motion pictures during this time deserve their fair recognition: Ruby Dee, Beah Carroll, Diahann Carroll, Diana Sands, and Abbey Lincoln. Neither of these women ever starred as a film’s main character alongside their male counterparts, especially with white actors, but it should be noted that these women delivered spectacular performances that remain memorable in the minds of filmmakers and audience members.

Black men saw increasing perceptibility but it was mostly Sidney Poitier whose fame skyrocketed allowing more Hollywood films centered on the young, Bahamian actor as his lead roles often bolstered his intelligent, handsome, and gentle qualities. The times were changing and America felt it. The Civil Rights movements swelled in the South and by 1969 Hollywood had finally produced its first film by an African-American, Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree. Still, Black women had to seek other avenues for control over their voices, images, and the stories they wanted to tell. It would take a couple of new doors opening a few miles away from Hollywood at UCLA before Black women could enter and create, along with promising opportunities in television and journalism.

L.A. anchored an impressive burst of creative activity that bobbed to the surface thanks to the rising number of attendees at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1966, the Dickers Art Center filled its department with creative expressions from members all over the African Diaspora. These artists were changing and expanding the landscape of art building on the past with their eyes on the future. From 1966 through the 1980s, a slew of artists and filmmakers entered the UCLA Fine Arts and Film departments and inadvertently mentored and aided one another in generating unique modes of expression unlike anything else of its time (Jones). The movement of filmmaking from these artists became coined as “The L.A. Rebellion” which swept through the 60s hitting a major peak in the 1970s and 80s.

This rebellion displayed itself through art, but more importantly through street rioting as the racial divide in L.A. sparked into a fiery incineration. The Great Migration of the early 20th century had sent a majority of African-Americans from the South into the North and Midwest largely bypassing the West coast. However, in the 1940s WWII spawned increasing defense production and labor in various departments in L.A. beckoning the call to many African-Americans to come for work. This resulted in the “Second Great Migration” in which L.A.’s black population rose impressively from 63,700 in 1940 to 763,000 by 1970. Black bodies throughout L.A. had now become a largely visible population, and right on cue with as the country focused on its racial divide and inequality.

Housing became increasingly scarce with the arrival of more residents and patterns of housing discrimination were fervent. Suburban white areas had pushed large numbers of African Americans and Latinos to South and East L.A. Land developers began constructing housing in the Compton and Watts neighborhoods resulting in Black suburbs that provided comfort for working families. By the 1950s, the boiling crime and racial divide in the city hit its tipping point. The Rumford Fair Housing Act passed in 1963, intending to end discrimination against African-Americans for housing, but Californians voted for Proposition 14 a year later which nullified the passage of the act and further expressing a desire to segregate California.

With these racial issues bubbling–including rage aimed at Martin Luther King’s assassination– Watts, L.A. imploded on itself sending a blast of radiation out to those across the city and country. A 1965 traffic stop of an allegedly drunk African-American driver resulted in a clash with police and citizens of Watts, L.A. The clash exploded into a six-day riot in which angered citizens expressed their rage of oppression into the windows of businesses and torched cars on the road. The riot made L.A. look a like a war zone culminating in $40 million in damage and 34 deaths. Hollywood, however, continued making films staring white faces as if nothing was happening.

Regarding the abscene of the Watts riots in mainstream media, even today, L.A. Times journalist Steven Zeitchik pointed out, “History hardly needs Hollywood for validation, and a movie can’t alter the trajectory of past events. Still, a film can enshrine struggle in our collective memory and even alter our perceptions. The absence of Watts movie footage suggests that pop culture has yet to fully process the complexities of our racial divisions — and, in turn, could inhibit the process from taking hold in the future.”

Meanwhile, African-Americans in selected areas of the country increasingly began to see more liberal and accurate representations of themselves and relatable issues through public broadcast news. New York’s own National Education Television (NET) acted a liaison that bridged stories affecting the African-American community to the masses. Among the network’s journalists was Madeline Anderson, whose own filmmaking turned a keen, powerful eye on to the social issues pertaining to African-Americans. Anderson’s co-worker and fellow documentarian St. Clare Bourne is heralded for doing the same. NET intended to rival the handful of networks that existed at the time (CBS, NBC, Dumont) and swiftly became a network that professed to make stories for black people by black people. But– as Anderson pointed out after a strike initiated by the network’s employees– NET’s first executive produce were white. “Why should someone always be interpreting our experience and not correctly?” Anderson pondered. By 1969, more creative control was delivered to the staff of NET as African-American William Greaves took over as executive producer, helping change the direction and creative output of the network.

Through NET, Madeline Anderson became one of the premiere Black female documentarians in America centering her work on social injustices and focusing on the lives within the Black community. In 1958, Anderson felt the need to capture the racial struggles taking place around her. While employed with Andover Productions, she began work on her first short subject documentary Integration Report: Part One. It is historically significant for its role in capturing protests in New York, Alabama, and Washington D.C. with protesters fighting for and against integration in the schools. The film features an inspiring, little-known speech from Dr. Martin Luther King as well as the fiery expression of pride and gratitude from Baynard Rustin to his fellow activists. Integration Report: Part One collects images captured by various photographers including soon to be famous directors D.A. Pennebaker and Albert Maysles. Anderson gained funding for her project by saving money from paychecks and receiving donations. Maya Angelou even offered to record “We Shall Overcome” with no charge for Anderson which begins and ends the film.

Through NET, Madeline Anderson became one of the premiere Black female documentarians in America centering her work on social injustices and focusing on the lives within the Black community. In 1958, Anderson felt the need to capture the racial struggles taking place around her. While employed with Andover Productions, she began work on her first short subject documentary Integration Report: Part One. It is historically significant for its role in capturing protests in New York, Alabama, and Washington D.C. with protesters fighting for and against integration in the schools. The film features an inspiring, little-known speech from Dr. Martin Luther King as well as the fiery expression of pride and gratitude from Baynard Rustin to his fellow activists. Integration Report: Part One collects images captured by various photographers including soon to be famous directors D.A. Pennebaker and Albert Maysles. Anderson gained funding for her project by saving money from paychecks and receiving donations. Maya Angelou even offered to record “We Shall Overcome” with no charge for Anderson which begins and ends the film.

In 1967, racial riots broke out in Newark, New Jersey after a black cab driver was arrested and allegedly abused by white officers. The production team of NET scrambled to cover the story with the network commissioning a documentary to be made about the upheaval. As time went on and NET became more centered in their coverage of Black issues, the decision was made to create “Black Journal, a once a month, hour-long “magazine show” that mixed video tape and film by various filmmakers and journalists working at the network. Anderson recalls “Black Journal” being a show that was inventive unlike anything before or since owing the show’s creativity and innovative depiction of images a result of their lack of funds and budgeting issues.

Anderson had to hustle screenings of Integration Report: Part One to churches and classes before gaining outside distribution. Anderson went on to work as an assistant director with Shirley Clarke on The Cool World in 1963. In 1967, she made a short, highly praised documentary about Malcolm X featured on “Black Journal” before she produced her most critically acclaimed and successful film I Am Somebody in 1970. Anderson’s success continued when she turned to producing and directing in children’s television, most notably “Sesame Street” and “The Electric Company”. Anderson’s work is considered to uphold many characteristics of Third Cinema, a movement in filmmaking that pushes for truth and encourages mass activism.

Black women in Hollywood had success, but much of their greatest achievements throughout the 1960s were in the realms of Broadway and Television. Diahann Carroll became the first Black woman to win a Tony award for her on stage performance in No Strings in 1962. Carroll also held the honor of leading the sitcom “Julia” in 1968. Julia, a widowed mom who worked as nurse in a doctor’s office and held romantic interests in well to do African-American men, marked the first time a series portrayed a Black woman in a non-stereotypical role. Black women continued to struggle for visibility and proper representation throughout the 1960s, but managed to jump over major hurdles to accomplish the deed of expressing and telling stories that pertained to them greatly juxtaposing the issues that Hollywood’s broad lenses glanced over. By the 1970s, these renegade artist’s battle did not perish in vain. These women helped usher in a new visibility of creative brilliance that finally received the recognition and praise it deserved in the latter half of the century.

Additional Citation:

Jones, Kellie. Now Dig This!: Art & Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum. 2011

The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2016) — Watch it Now

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party. For most of us, this historical fact would have been swept under the rug and largely ignored had Beyoncé’s stirring performance at the Super Bowl not brought the Party back into the mainstream consciousness. Donned in leather outfits with black berets garnishing their afros, Beyoncé and her crew of female dancers reminded the world of the power once held by the revolutionary group, but the Super Bowl performance’s focus was only the Party’s aesthetic. The Black Panthers’ potential in dismantling America as we know it today during their reign has gotten lost in the translation of their history to the younger generations.

That’s not an accidental blunder. To my delight, I was lucky enough to enjoy continuous enlightenment over the weekend at a Black activism conference at Emory University. There, Ebony magazine Senior Editor, Jamilah Lemieux, stood as the keynote speaker further dropping knowledge on all of us who stayed to listen to her cultural critics and discussions on intersectionality. Raised by a Black Panther, Lemieux poignantly assessed much of this generation’s summation of The Black Panther Party. Our knowledge of the Party has been limited to phrases, slogans, and slivers of their empowering message that had gotten watered down over the years: Free Huey, Angela Davis got arrested for something so Free Angela. Kill the pigs. Wear berets. Feed the kids. Something like that.

To dig deeper into the Party, their intentions, and how they almost accomplished a complete toppling of the white supremacist system, one should turn to PBS’ brilliantly constructed documentary, The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. The film highlights the key players within and of the Party, their functions within the Oakland community, and how their universal themes of freedom from oppression and community assistance streamlined into major cities all across the country. Through a collection of footage, FBI files, present day interviews, photographs, and valuations within the documentary, Stanley Nelson Jr. commemorates those who fought long and hard in the movement only to get halted and terminated by a government hell-bent on keeping the status quo.

Nelson’s major achievement, which sets The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution apart from every other Black Panther Party documentary, is how he highlights the sobering meddling that J. Edgar Hoover and the government had in deflecting the impressive progress that the Black Panther Party had attained. The powers that be thought they had The Civil Rights Movement for social change controlled with the death of Martin Luther King Jr. Nevertheless, The Black Panthers picked up where the Civil Rights Movement left out, and though peace ceased to act as the forefront of their message, the Panthers carried the torch in the fight for a change of systematic norms.

Katherine Cleaver, Huey P. Newton, Fred Hampton, Bobby Seale, Bobby Hutton, and hundreds of others across the country endured bodily harm, phone tapping’s, jail, sting operations, and set ups by authorities. Yet, they continued to shout through gagged mouths in courtrooms, unify across the world, protect themselves and others, and provide services for their community that the government refused to do. The Black Panther Party weren’t trying to appeal to the masses by sending feelings of fuzzy joy and peace to make a statement. The Hippie movement tried that and shootings at Kent State, among other moments of government noncompliance, showed these methods don’t work.

The Party wanted to uplift members of the African diaspora and remind them of their own influence and beauty. The government possessed resources that proved too powerful, however, and it worked hard at stifling that message and dismantling The Black Panther Party leaving remnants of their memory behind. Everyone needs to take the time to watch this documentary so that history can stop repeating itself and we can break the chains of inequality and the status quo of injustice once and for all. 2016 is the year to pick up the broken pieces from those before us. We have the ability to reconstruct those pieces and make them stronger than ever, so let’s take responsibility and pay back those before us by doing so.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

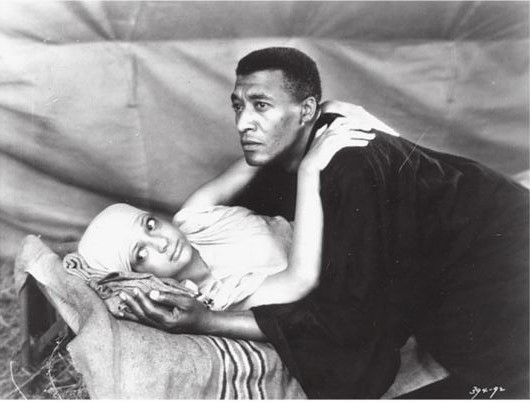

By the end of the 1950s Dorothy Dandridge’s career fell into a stalled slump. Her private life received copious amounts of sensationalism as she developed a dependency on prescription drugs and alcohol. To deflect her personal problems and return to work, Dandridge broke her hiatus in 1957 starring in her last three major motion pictures. The most notable of them all, and arguably her career, is the most forward-thinking, controversial film of the decade, Tamango. Though just a Hollywood actress, Dandridge used her super stardom to transform Tamango from what she initially called a “shipboard sex drama, tawdry, and exploitive” into a powerful tale ahead of the times in an extraordinary way (Cowans 323).

A Franco/Italian collaboration, Tamango is a bold adaptation of the 1829 French novella of the same by Prosper Merimee which chronicles a slave revolt on a Dutch ship. Dandridge takes on the part of Aiché, a mixed-race slave on the ship and concubine to her master, the ship’s captain. Tamango unfolds through the eyes of Aiché and the ship’s newest onset Tamango, a lion hunter from Africa who is determined not to arrive on land in chains as a slave. Dandridge plays up her physical beauty, but brings a strength and griminess to her character that isn’t seen from her previous roles in Hollywood. Aiché begrudgingly knows her place among the whites on board, and yet she also feels a strong pull to her race and fellow slaves, a connection that is deepened with the arrival of Tamango.

Tamango’s director and primary screenplay writer, John Berry, had been an established Hollywood director by the late 1940s; that is until the bullying boogeyman of Hollywood, the HUAC, stripped him of his merit after director Edward Dmytryk named Berry, among others in Hollywood, as a communist to clear his own name. This hindered Berry’s career and sent him into exile in France. Despite Berry’s once successful status as a Hollywood director, Dandridge had no qualms with implementing a direct say in much of the film’s development. She took on a role similar to that of a producer by making drastic changes to the script giving integrity to the character she was to portray. Dandridge helped transform Tamango from an atypical exploitation film into a piece of subversive art with a powerful tale to deliver.

Merimee’s original story stifled the character of Aiché into a box where her husband Tamango drunkenly trades her to the ship’s captain out of anger. Aiché’s role is nothing more than a catalyst for Tamango’s motives to get her back therefore advancing the plot of the story. Berry’s script virtually placated Dandridge into this role with intentions of using her physique to steam up scenes of the film by creating a love triangle of sorts between Tamango, Aiché, and her white slave master. Dandridge, unsatisfied with this notion of her character, pushed Berry and the film’s other writers to make her role more confrontational in which they obliged (Cowans 323).

Tamango’s costume design also caused tension between Dandridge and the creators behind the film. Berry’s son, Denis, recalls how his father’s issues on set were largely due to his ignorance of the European culture and the collaborations within it. Berry hired fashion designer Madame Carbuccina, who in turn used costumes designed by contemporary Parisian designers. The film’s assistant director, Jaques Nahum, recalls the outfit that Dandridge originally was meant to wear being so skimpy that it looked like something a Madi Gras dancer would wear. Dandridge apparently took one look at them and refused to do the film (Prime). Dandridge only agreed to continue with the project when the wardrobe matched her liking resulting in the full-bodied dress and headscarf that she wears throughout the film.

Despite the contention between Dandridge and Berry, their compromises make for an engaging powerful film ripe with tenacity and intrigue. Berry’s screenplay highlights the hypocrisy of the mentality that allowed slavery to exist, as the Captain proudly intends to treat his slaves well and respectfully, such as in one scene when he scolds the ship’s cook for the unappetizing food that his slaves have to eat. Nevertheless, the Captain still utilizes the institution of slavery to keep himself at an advantage and the men and woman on his boat are subjected to his rule. The script allows Dandridge to deliver more sustenance to her role than the stereotypical surface dramas she had participated in Hollywood.

Here, Dandridge’s character is more complex and evolves changing mindsets and hearts as the film continues. Aiché is given the freedom to deliver a powerhouse speech in which she channels her rage for being branded and beaten by white masters to the Captain who is ignorantly shocked at her disdain. He has convinced himself that he is a just and “good” master, to which Aiché reminds him why he’s scum. Frequently throughout the film, Aiché’s hair is long, blowing in the wind. She combats this by wearing a headscarf but the Captain always makes a point to displeasingly take it off her. She later expresses to him how her hair down and flowing is merely something for his pleasure, a way to see her as a white.

It almost seems natural that a film of this stature so ahead of its time would get banned upon release. Dandridge’s popularity couldn’t excuse the film’s powerful anti-white supremacy stance in a time where much of the world was shrouded in the mindset that Blacks among other minorities were somehow less than. Berry’s script is rich with humanity and raw honesty. Tamango touches on the greed and selfishness of humans as the slave trades are shown to be possible with the cooperation of an African chief who trades his people for guns and rum. Berry’s collaborative screenplay provides backstories for the slaves, character development to side players, and a voice with which the marginalized can express their disdain for the life they have been forced to enter. Dandridge’s refusal to participate in a film in which the original script did not have these elements is a telling aspect.

But, it wasn’t enough for audiences to welcome the story with open arms. Many American critics discredited the film for its focus on slavery and its time period. French audiences fared better, though not by much, as critics were mostly negative in their reviews of the film as well (Cowans, 325). Tamango’s production took place in Nice, outside of French cinema jurisdiction, and yet the film still got banned in colonized parts of France for fear that it would “rile up the natives.” Most critics couldn’t get past the film’s overt shameless depiction of an interracial affair between Aiché and the ship’s Captain. In America, Tamango got trimmed and pruned to a limited release but completely diverted a release in the South.

The ugly reality of racism and slavery was not something that audiences and producers of the era were ready to confront. Tamango shatters all of this by doing everything they weren’t supposed to do and the result is a film with real emotion and a gut-wrenching story. Tamango marks the first time the subject of slavery was shown in gruesome, harrowing detail and it would take another 20 years before the subject received further exploration in Alex Haley’s television adaptation of “Roots.” It would then take another 20 years after that before Hollywood would make Amistad expanding on Tamango’s broad imagery of a slave revolt and expounding on the conviction of a people forced into a degrading lifestyle.

SEE IT.

Additional Citations:

Cowans, Jon. Empire Films and the Crisis of Colonialism, 1946–1959. Maryland: John Hopkins University Press. 2015.

Lawrence, Novotny. Documenting the Black Experience: Essays on African American History, Culture, and Identity in Nonficition Films. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc. 2014.

Prime, Rebecca. Cinematic Homecomings: Exile and Return in Transnational Cinema. Bloomsbury Academic. 2014

The Rise of Television, Black Visibility, and the Illusion of Creative Control in the 1950s

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

Within the span of about 30 years the motion picture industry dramatically changed. What was once a filmmaker’s haven in the 1920s where amateurs, professionals, and those in between could make their own films and distribute them how they wished had become a system locking certain people in place to make films while excluding others by the 1950s. The earlier days of filmmaking had welcomed a host of talent ushering in men, women, Asian-Americans, and African-Americans. One’s personal background didn’t matter as much as their ability to raise the money needed to display their stories through the flickering light of a projector.

By the 1950s, white men and the stories they chose to tell dominated the avenues of filmmaking with such authority that it virtually barricaded unfamiliar voices from outside of the studio system. Independent filmmakers still thrived inside and outside of the system though the outsider’s numbers remained diminutive. Despite the power that Hollywood held during the late 1940s into the 1950s the struggle for relevancy and profit rose with the arrival of television. Arriving in the 1940s and exploding in the 1950s television quickly became another facet for exploration of Black characters yet little, if any, creative control was given to women or people of color.

Black women found navigating through cinema and television to be a slippery slope with many hills to climb and dull support to hold on to. Many of the working Black females in Hollywood found bit parts in movies sticking to roles that had been around for decades. A handful received more promising opportunities as all-Black cast films continued throughout the 1950s and a small amount of meatier roles opened up to a select few. With television taking off only a miniscule group of Black women stood front and center as drivers for their own vehicles, though their efforts would be short lived.

At the start of the decade acclaimed jazz pianist and singer Hazel Scott made waves by becoming the first Black woman to star in her own variety show on a major network station. The Trinidadian-born Scott’s talent and vivacious personality earned her a spot on the Dumont Network starring in the “The Hazel Scott Show”. Scott’s program included the performer singing show tunes and other songs along with comedy bits and routines in a 15-minute time slot that aired Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Scott’s show received average ratings from the fading Hooper rating system and great reviews amongst critics. That failed to help the show thrive when a mere two months after its premiere Scott found herself on the Red Channels list. Her outspoken nature and brash discussions on civil rights had made her a target in age of McCarthyism. Though she voluntarily appeared before the HUAC to defend her performances and appearances at rallies and fundraisers for various organizations, the damage was done and sponsors pulled from her show rendering it cancelled.

Scott’s apparent controversial nature also affected her time in Hollywood. Like many women with conviction who stand up for their values, Scott had a reputation of being difficult, one that she even spoke of in a profile of herself in “Ebony” magazine. “For much of my life, a great many people considered me conceited, stuck up, standoffish or what have you. This was because of my shyness. Some of my close friends insist that I am impossible. They say that I will not be serious. They are quite wrong. They just don’t understand. When I want to be serious, I am very serious. Most of the time this whole pose of not caring is just protective coloration.” (Scott, 144).

She clashed with Columbia Pictures mogul Harry Cohn while filming Rhapsody in Blue in 1945. Scott became outraged by the stereotypes and lack of visibility for African-Americans within the film. Rhapsody in Blue is a biopic of the life of composer George Gershwin, an actual friend of Scott. Although Scott was hired to play the role of a French pianist that inspired Gershwin, her part got minimized as studios wanted to keep the film safe. In doing so they gradually cut scenes from the film featuring other Black characters while also expelling the role of Armenian born Broadway director Rouben Mamoulian from Gershwin’s life. Producers also kept the film’s leftist original screenplay writer, Clifford Odets, uncredited. Scott’s dissatisfaction with the producer’s choices made her “haughty and high-minded”, but her anger at the film’s lack of diversity and unwillingness to showcase talent due to preconceived notions of race is justified and powerful. Scott declared that she never made another Hollywood film after Rhapsody in Blue (Regester 225-227).

Actresses Louise Beavers and Hattie McDaniel still found steady gigs in Hollywood films during the 1950s and were among the few actors of color who transitioned into television. McDaniel was a notable star and paid handsomely for her part in the radio comedy series “Beulah” three years prior to the show moving into television. The sitcom followed the wise-cracking house maid of a white family. Once again, McDaniel was forced to play the servant to white families. McDaniel took the lead role of the television series in 1951, but fell ill to breast cancer and couldn’t finish shooting leading Ethel Waters to take her place and film the first season. Waters quit the show the same year resulting in Beavers taking on the role of Beulah. Each of these actresses possessed immeasurable talents and had become legends in Hollywood, but they were unfortunately subjected to playing a maid for the masses to watch and laugh at.

Former Gone with the Wind actress Butterfly McQueen also guest starred in the show as Beulah’s friend, though much like McDaniel, she played virtually the same role as before in Gone with the Wind and all the other roles that followed it. “I didn’t mind playing a maid the first time, because I thought that was how you got into the business. But after I did the same thing over and over, I resented it. I didn’t mind being funny, but I didn’t like being stupid” McQueen said of her role choices. “Beulah” got met with great criticism from members of the NAACP and Black viewers who felt that McDaniel’s role was the stereotypical “mammy” that had become synonymous with large, sexless black women.

Meanwhile, Dorothy Dandridge emerged in Hollywood becoming an overnight sensation after her performance in the all-Black cast film Carmen Jones alongside fellow Black actresses Pearl Bailey and Diahann Caroll. Carmen Jones became a box-office smash sending Dandridge into super-stardom. She received notoriety as the first African-American nominated for Best Actress rivaling Grace Kelley, Audrey Hepburn, Judy Garland and Jane Wyman. Dandridge also received a BAFTA nomination for Best Foreign Actress. She went on to sign a deal with 20th Century Fox studios, but quickly faded from the limelight towards the end of the decade.

Dandridge is often one of the few Black female figures thought of when 1950s Hollywood comes to mind, but to uphold Dandridge as if she was the first of her kind and a premiere talent of the era is a great disservice to the talents that emerged from the period. Eartha Kitt arose in the 1950s giving a stellar performances most notably in the incredible, yet underrated Anna Lucasta. Kitt’s contemporaries also included Ruby Dee and Pearl Bailey who were each featured in a string of films throughout the 1950s, along with actresses Juanita Moore, Diahann Carroll, and Beah Richards. The iconic films harboring the talent of these women were Carmen Jones, Take a Giant Step, Porgy and Bess, and St. Louis Blues.

Overseas in London, writer Sylvia Winters began to cement her name in history after graduating from the University of Spain in the early 1950s. Though born in Cuba, Winters was born of Jamaican parents. She moved to London later in her life where she was given the opportunities to create and adapt radio drama for BBC’s Caribbean Voices and Third Programme. Both of these radio shows focused on highlighting written works from West Indian writers along with discussing racism in parts of South African respectively during the 1940s and 1950s. Winters also had a hand in creating the radio drama “The University of Hunger” with her then husband Jan Carew. Together the duo impressively completed the stage play “Under the Sun” which got bought by the Royal Court Theater in London. Winters is one of the few women of color creating their own content during the 1950s and her career only continued to reach new heights throughout the 1960s and 70s as she moved away from dramas into critical discussions and essays.

Within Hollywood, England born actress Ida Lupino maintained the status of the only female directing films during the 1950s (Stanley 45). The actress fell into directing by chance when on suspension for turning down a role. Lupino was a rarity in Hollywood as no other women could yet reach the glass ceiling she found her own self bumping against. Women of color in America found it impossible to even grab the heels of Lupino to direct, write, or produce their own pictures. More creative control was slowly becoming allotted to women of color, but it would still be another few decades before the control was fully theirs.

Additional Citations:

Regester, Charlene B. African American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility, 1900-1960. Indiana: Indiana University Press 2010.

Scott, Hazel. “Ebony Magazine.” September 1960 Volume XV No. 11. A Johnson Publication.

Stanley, Richard T. The Eisenhower Years: A Social History of the 1950’s. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse 2012.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

The film industry underwent a major shift during the 1940s, one that changed the type of films getting pumped out to the masses and who could create them. As the studio system rose to prominence it crushed most of the independently operated studios across America leaving only a handful outside of the system operating with success. Hollywood became the titan of the sea ruling over the filmmaking business like never before. All other competitors were virtually washed away.

Only two African-Americans managed to drift through the 1940s directing their own films, but Spencer Williams and Oscar Micheaux relied heavily on the aid of small white-owned production and distribution companies. The left a single Black studio floating adrift producing its own films for Black audiences and that was William D. Alexander’s Alexander Productions. Through the effort of these men’s creative output and Hollywood’s foray into making all-Black casted pictures, Black women endured lengthy screen time to an extent, but men, more specifically white men, continued to run the filmmaking business.

William D. Alexander and Jazz bandleader Anne Mae Winburn

Having previously worked in radio while in Washington D.C. and expanding into journalism through the Office of War Information, Alexander became the only African-American who could afford to keep a studio and produce films of his choice during the 1940s. Though most of his productions were musical shorts, his feature-length films were a mixed bagged of all-Black coupled with interracial creative efforts. Alexander is credited as having made the last “Race film” by a Black producer in 1949 with the socially investigative film Souls of Sin.

Meanwhile, director Oscar Micheaux couldn’t compete financially with the films that Hollywood was making forcing him to momentarily leave the business and resort to writing novels. Micheaux returned to filmmaking in 1948 to make The Betrayal with the help of the white-owned Astor Productions. What he hoped would be his magnum opus was instead a box office disaster. The financial loss of the heavily panned film was so severe that Micheax left filmmaking all together to sell his novels for income before passing away two years later in relative obscurity.

Gerald Horne notes in his book Class Struggle in Hollywood, 1930-1950 that women of all races working in the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) union suffered during the 1940s. Their work got depreciated to jobs that society assumed women should have: office work, hair styling, costuming, entry-level animation, and make-up. Actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee were reportedly shocked at the lack of African-Americans working in Hollywood when they entered the scene in the late 1940s. They recalled from the moment they “entered the gate in the morning till the time we left, we were in an all-white world, and that reality was hard for us to ignore” (Horne, 52).

Although their representation and depth of character remained dismal in Hollywood films, African-American female entertainers thrived outside of the boxed-in system of the time period. The Cotton Club in Harlem, among other night clubs, housed phenomenal talent as did the theater groups of New York. Many participants in the entertainment scene of New York would go on to become well-known actresses of the time such as Isabel and Fredi Washington, Dorothy Van Engle, Mae Turner, and Francine Everett. Broadway became a hotbed of activity for Black performances as well. Stage actress Ethel Waters became the highest paid performer before her transition into film.

Independent films outside of the studio system gave Black women a visibility that the roles of maids, mammies, tragic mulattoes, and background faces did not provide in a majority of mainstream pictures. Suzette Harbin, Hilda Simms, and Marguerite Margaret Whitten are just some of the many actresses that lit up the screen with starring roles in “Race films” during the 1940s. But, the split personality of Hollywood’s struggle for racial acceptance began to show during the decade. For every step forward Hollywood took, it forced itself back by two more.

Lena Horne became the second African-American woman to sign a contract with a major studio. She received massive attention turning heads with her poised, tenderly sweet voice in minute parts of mainstream films and starring roles in Cabin in the Sky and Story Weather, Hollywood’s biggest all-Black films. Though Horne possessed a very light complexion that almost made her indistinguishable from her white co-stars, the construct of race was, and continues to be, so heavily veiled that certain scenes of her films were shot separately so that studios could easily cut them out for Southern audiences. Horne’s role choice was limited due to production code rules in place that forbade miscegenation, sexual relationships between races, once again leaving a human being’s career and future hanging by a string because of race.

Turbulent times rocked the country throughout the 1940s affecting the film business on a large-scale. World War II was at its height which promoted Hollywood propaganda on behalf of the war effort. Communism became the hot topic on everyone’s lips resulting in the HUAC hearings that blacklisted ten prominent filmmakers and destroyed the careers of many more including famed African-American actors Paul Robeson and Harry Belafonte. By the end of the 1940s, Horne’s name appeared in the Red Channel, a right-wing pamphlet accusing various entertainers in the industry of being communist sympathizers in the age of McCarthyism. Horne’s career didn’t advance too far in Hollywood due to the controversy, though her immense popularity and civil rights activism in later years have contributed to her legacy.

Hollywood experienced a bit of an identity crisis during the 1940s. On one hand, Hollywood created three of the biggest films featuring an all-Black cast; The Green Pastures, Stormy Weather, and Cabin in the Sky. Yet, stereotypical portrayals of African-Americans and insensitive ideals based on race still swelled on the surface of these pictures. To this day The Green Pastures is criticized for its stereotypical view of African-Americans. Likewise, Walt Disney produced Songs of the South in 1940, a film that has continued to be shrouded in controversy since its premiere and still has not received a home-video release because of it.

The absence of colorful faces in Hollywood during the 1940s fell from immediate thought of most of the whites in charge of jobs and pay in Hollywood. Their focus centered on trade agreements, union battles, and staying safe for the sake of profit. The Conference of Studio Unions (CSU) manifested during this time period in which set decorators among others of the IATSE broke off to join the CSU in hopes of better wages and contract negotiations. When neither happened the workers went on a six-month strike in 1945 before anger turned into a bloody week of rioting, flipped cars, L.A. police teargassing patrons, and a meaty news worthy topic for the public to chew on. By the time the CSU disbanded only a whopping 10 of 9,635 weekly studio employees were African-American. There wasn’t a single African-American secretary, accountant, prop man, grip, reader, cutter, or art director in the motion picture industry (Horne, 52).

Nevertheless, Ethel Waters, Horne’s co-star in Cabin in the Sky, enjoyed a fruitful decade that ended with her Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress in Elia Kazan’s 1949 film, Pinky making her the second Black woman nominated. Waters and Horne walked tall during the 1940s in spite of the hurdles that stood in their way by systems meant to keep white creators and performers at an advantage. But, it is important that we do not forget the incredible, often forgotten, or blatantly ignored, talents that worked steadily throughout the decade despite their ability to find mainstream popularity. Immediately one can see the stark effects that lacking production values had on the films made outside of the system during the 1940s , but Everett, Van Engle, and Whitten are the few among many talented African-American women who took subpar scripts, amateur filmmaking techniques, and tacky, harsh lighting of the films they starred in and shined an illustrious greatness into them. These women should be remembered for their talents during a time that attempted to shun and silence them.

Additional Citations:

Horne, Gerald. Class Struggle in Hollywood, 1930-1950: Moguls, Mobsters, Stars, Reds, and Trade Unionists. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001.

The Fading Creative Control of Black Women in the 1930s

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

The rise and popularity of the Harlem Renaissance throughout the 1920s into the 1930s assured the presence of many African-American women in multiple facets of entertainment. Jazz and the Blues bubbled to the surface of mainstream radio bringing with it singers Bessie Smith, Alberta Hunter, Victoria Spivey, and Billie Holiday to the consciousness of American consumers. Authors, journalists, and poets– including Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Nelson Dunbar, Jessie Fauset, Eulaice Spence, and Anne Spencer– exploded on the scene writing their truths and promoting equality for women and African-Americans. Yet film, the most easily digestible and among the most popular medium of the time, still continued to stifle the role of Black women both on screen and behind the camera masking and limiting their representation to the masses.

The illustrious success that many African-American women found in front of the camera is owed to the African-American studios that produced them outside of the Hollywood studio system. It is truly unfortunate that many Black studios folded under the weight of The Great Depression forcing most of the directors, producers, and actors who worked before the crash to return to trade and service work. For the lucky handful that continued on in the filmmaking business, their prominence didn’t extend past the African-American audiences who went to watch the “Race films” they appeared in. Within Hollywood the roles for Black actors were limited to servants or uncredited parts.

Singer and dancer Josephine Baker endured longevity and brought in the most expansive crowd as she became a cultural phenomenon in the 1920s. Baker went on to star in seven film during the late 20s into the 1930s, yet despite her irresistible sexuality and glowing persona she couldn’t break through America’s strong hold on racism preventing her from a becoming a breakout actress in the states. Baker’s three biggest films– Siren of the Tropics, Zou Zou, and Princess Tam Tam– were all French productions. She became a French citizen in 1937 and embraced the popularity she received in the country and in neighboring parts of Europe.

While Baker found success overseas, those who faired for recognition in American found the task much more difficult. The handful of African-American actresses known to lead feature-length films as opposed to short musical reels during this time were Alice B. Russell, Dorothy Van Engle, Fredi Washington, Ethel Moses and her sisters Lucia and Julia, Louise Beavers and Hattie McDaniel. Of these women only three had extensive and recurring roles in Hollywood films, and only one got the chance to play more than a maid in a role.

Fredi Washington’s light complexion gave her the advantage of playing Peola in John M. Stahl’s 1934 drama Imitation of Life, a film that 25 years later would get remade and recast with white actress Sarah Kohner revising the role. To add insult to injury, Kohner was nominated for an Oscar for her role as a light-skinned Black woman who passes for white. Washington’s dexterity and wonderful acting skills haunted her throughout the years as the question of her own passing continued to be brought up, as many assumed that she passed in her actual life. Washington replied to the sentiment by stating:

“Why should I have to pass for anything but an artist? When I act, I live the role I am assigned to do… I don’t want to “pass” because I can’t stand insecurities and shame. I am just as colored as any of the others identified with the race.”(Regester, 123)

Unfortunately for Washington, she was considered too light to play a maid and too dark to play a love interest in a major Hollywood film stifling her career to a standstill.

Black women seem to have possessed very little creative control in the representation of their stories and lives except minimally on the stage. In 1915, an African-American dancer, singer, and stage actress Anita Bush succumbed to a back injury that put her out of commission as a dancer, Having grown up in the theater, she set her sights on drama and founded the Anita Bush All-Colored Dramatic Stock Company. She wanted to prove to the masses that African-Americans could be serious actors and not just vaudevillian singers and dancers. On a whim, Bush offered her services to then owner of the newly renovated New Lincoln Theater offering to give the theater a play in the upcoming weeks. When her offer was accepted, Bush went out gathering an ensemble of actors and writers becoming the first group to operate in the New Lincoln Theater in New York City (Kennedy).

Bush’s company subsequently changed its name to The Lafayette Players when the company moved buildings, but that didn’t dim the power of Bush’s eye for talent. The company throughout its reign would cast Evelyn Preer, Lawrence Chenault, Paul Robeson, Charles Sidney Gilpin, among other prominent Black actors who would go on to star in Broadway plays and films in the 1920s and 1930s. The Harlem Renaissance gave resonance to the theater group’s existence. The Lafayette Players were divided into four groups that performed serious dramas regularly in Chicago, New York, up and down the East Coast and throughout the South. Ahead of their time and with The Depression looming, the company faded from existence, leaving its legacy in the actors that participated in it.

Bush laid out a path and opened the door for more African-American women to step through including Ida Anderson, Abbie Mitchell, and Evelyn Ellis. African-American Broadway actress Rose McClendon appeared in a slew of on stage productions before taking the reigns as director in 1935 when she co-founded The Negro People’s Theatre in Harlem boasting over 4,000 attendees at its first production of Waiting for Lefty. McClendon’s prominence became cemented when the Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project formed under her supervision. FDR’s New Deal reform to help America out of the Depression allowed McClendon to guide the creation of theater units in Seattle, Philadelphia, Newark, Los Angles, San Francisco and Chicago.

McClendon also advised that the project begin under the direction of Jon Houseman who served as her co-director. A year later Houseman would go on to enlist the directorial lead of a then 21-year-old Orson Welles to direct a play for the company. Welles’ choice was to make an aptly nicknamed “Voodoo Macbeth”, a retelling of Shakespeare’s famous play loosely based on Haitian revolutionary Henry Christophe and set in Haiti with all-Black cast that opened in 1936. McClendon was set to play Lady Macbeth but suffered from chronic sickness that would take her life that year. McClendon’s role in the project, however, resulted in Welles producing one of the most discussed plays of its time, a box office smash, and a halo over his career before going on to direct the greatest film of all times (Flanagan).

By the end of the decade Hattie McDaniel went on to become the first African-American woman to receive an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in Gone with the Wind. Though the win would be a huge achievement for Black women in Hollywood it also halted progress to a grinding stop. McDaniel bathed in the glory of a win but still suffered from the reality that she had to to sit separately from her white co-stars during the ceremony. It would take another 50 years before another Black actress would receive the award and 60 before Halle Berry became the first and only African-American to win Best Actress. Even still, creative control under African-American women was still minimal at best during this time period, and though more Black actresses would rise to fame in the 1940s, their role behind the camera was completely wiped out.

Additional Citations:

Regester, Charlene B. African American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility, 1900-1960. Indiana: Indiana University Press 2010.

Flanagan, Hallie (1965). Arena: The History of the Federal Theatre. New York: Benjamin Blom, reprint edition 1940.

Hallelujah (1929); And the Highlight of African-American Actresses in Early Hollywood

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

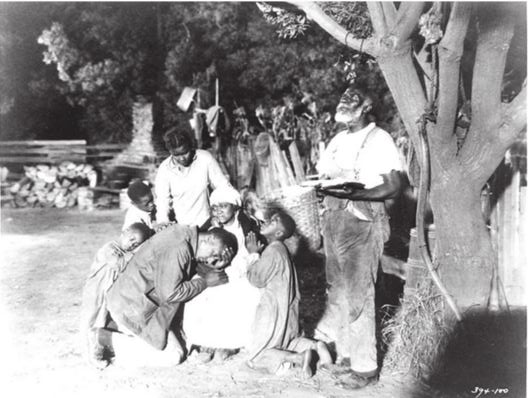

By 1929, dozens of films starring African-Americans that centered on their stories illuminated the screens of theaters throughout the country. Most were shorts, musicals, questionably racist ethnography films, and features from all-Black production studios. Sadly, based on current knowledge, not a single film from this period was produced or helmed by Black women. Hollywood soon decided to try its chance at dipping into the production of “Race” films. These were films aimed at attracting larger groups of minorities through all-inclusive casts of African-Americans and Chinese-Americans. Hollywood studios made two films that year, Hearts in Dixie and Hallelujah. Although these films were white productions, Hallelujah was the only to present Nina Mae McKinney to the world, Hollywood’s first Black actress, while also featuring Blues singer and songwriter Victoria Spivey as the film’s supporting actress.

Many of the films featured in 1929 are deemed lost rendering it impossible for contemporary viewers to see them. My focus will tighten largely on Hallelujah, the most famous of that year and most accessible to watch. Hallelujah shamelessly promotes the beauty and talents of African-American women when other films in Hollywood couldn’t even conceive the thought to do so. At the heart of Hallelujah’s story are the joys and sorrows of a Black Southern family and its oldest son Ezekiel (Daniel L. Haynes).

Hallelujah was met with mixed reviews for its portrayal of African-Americas during its release to the public. The same mixed feelings then has and will continue to permeate contemporary audiences today. But, despite its controversial portrayals, I think it’s important to stay open-minded when viewing Hallelujah and to see it as a relic of its time that possesses great importance like none before it.

Hallelujah and Hearts in Dixie distinguished themselves through two important attributes. Released just months apart, both were Hollywood’s first “all-Black” casted films as well as some of the earliest “Talkies” when Hollywood transitioned over from silent films into sound. Mutually, these films were directed by white men with careers already established in Hollywood. Nevertheless, both heralds notable achievements setting them apart from the rest of Hollywood’s films at the time.

King Vidor’s Hallelujah was a conscious attempt by the director to create a film that accurately portrayed the Southern black family. Vidor enlisted the help of Hollywood’s only female screenwriter at the time, Wanda Tuchock, to assist with the screenplay and casted the talented Nina Mae McKinney as Hallelujah’s lead. The male exclusive production of Hearts in Dixie doesn’t bar it from its own personal acme. Larry Richards’ African American Films Through 1959 lists the film’s staring actor, Clarence Muse, as having aided in the direction of the film, an uncommon aspect in Hollywood in 1929.

The first twenty minutes or so of Hallelujah is very hard to swallow. A Southerner by birth, Vidor’s earnest intentions were to produce a film that showed African-Americans as fair and true to life as he could. Vidor’s idea for Hallelujah bore from a secret hope he held for years of producing an all-Black casted film about Southern life. His idea got turned down by studios every time he mentioned it. Once sound hit Hollywood in 1927 with The Jazz Singer, Vidor seized the opportunity to make his dream film a reality. He so strongly believed in his concept that when studio executives feared the lack of revenue for not attracting enough white audience members, Vidor offered to forgo his own salary to make the film. The studio reluctantly allowed him to make Hallelujah.

But, while some reviewers praised the film after its release others condemned it. As one New York reviewer said of the film to Amsterdam News:

“After the picture was well under way on its opening night, it was clearly to be seen that the superb acting of the cast was being over shadowed by the amount of spirituals, meaning the weeping and wailing and the weak, the love [in] spirit were dominating the picture. When one sees “Hallelujah,” stripped to the bone and laid bare it is not hard to imagine why Harlem is the largest Negro City in America, why Chicago, Philadelphia, and Baltimore and the others are increasing in Negro populations. “Hallelujah” is the answer.” (McAlister, 321)

At first glance, Hallelujah seems to uphold all those old stereotypes of African-Americans which is bittering and indignant to witness. We watch as Black bodies line the cotton fields of Memphis, Tennessee picking cotton and singing out spirituals and hymns with an unbelievable joy and sprite that doesn’t fully reflect the plight endured by those who may have been born into slavery, freed by the Emancipation, and had to resort back to cotton picking because rampant racism and segregation left day labor jobs available to primarily African-Americans.

Once we leave the cotton fields Vidor invites audiences into the homes of the African-American family we are following. They sit for a meal of chitilins and spare ribs and their oldest son, Ezekiel (Haynes), brings out a banjo while the family engages in an after dinner jig with the youngest of the family tap dancing on tables as they all sing together. Now right here, it was very hard for me to continue watching. My annoyance at these portrayals grew as I expected to hear the demeaning words “yes massa” and “I sholl do love pickin cotton” along with other horribly racist images and vernacular that was all too present in the time period. These caricatures have gotten singed into the general consciousness of society for decades. So much so that many of us are actually ashamed to eat fried chicken in public and even utter the word “watermelon”.

Photo courtesy of “Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies”

But, Vidor doesn’t allow Hallelujah to live up to these expectations though it certainly seems to flirt with it. A white man who grew up with an African-American matriarch in his home, Vidor admitted in an interview that he wanted to dedicate the film to the woman who was more of a mother to him than his own (Manchel, 330). Though his portrayals are cringe worthy they speak of the time period in which Vidor grew. At 34 years old he made Hallelujah based off the experiences he had in adolescence. In that 30 year period a world of change developed quickly for the Northern half of the country due to Reconstruction and The Great Migration.

These moments of cringe worthy portrayals exist throughout the film due to the melodrama of the film itself, but they stop feeling like caricatures and start developing into what they were intended to be; representations of life in the South overdramatized by music in an era when sound boomed in Hollywood. We watch as Fanny Belle de Knight, the film’s matriarch, rocks her children to sleep with a sweet, soul-satisfying lullaby given us a homely view of these people’s lives. There’s humor within this family as they joke and pick on one another and they celebrate the union of neighbors with a wedding song and dancing.

A scene in particular that caused me to squirm in discomfort came when Ezekiel irrepressibly forces a kiss on Ms. Rose (Spivey), his house mate who he’s attracted to. Immediately this scenes conjures up the stereotype of the “Black Buck,” a male unable to control himself usually at the sight of a lily-white woman. Yet, again Vidor crushes these expectations by making the object of his desire a Black woman and immediately Ezekiel regrets his impassioned actions and apologizes to Rose. This scene becomes an indication of things to come and a look into Ezekiel’s individual personality as opposed to a stereotype on all black men. This act of passion is foreshadowing for the situations that happens to Ezekiel later finds himself from not being able to control his emotions.

Photo courtesy of “Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies”

Zeke’s hard work ultimately grants him pay of $100, a sizable amount of money that he takes to a local club to celebrate with. This is the scene where the representation of African-Americans expands shifting the focus and that unsettling feeling I initially had throughout the start of the film. Here we see a host of dapper, well off African-Americans listening and dancing to Jazz music and finally we meet Chick (McKinney), a “Femme Fatale” of great beauty and a bubbling personality. Vidor has no shame in focusing on the beauty of McKinney through close-ups of her face, legs, and keeping her centered in the action.

From here the story follows a row Ezekiel has at the club when he gets swindled of his money. His inability to control his emotions causes him to shoot a character and painful regret he endures turns him into a man of God. Ezekiel’s search for divinity and forgiveness for his actions triggers impassioned sermons that attracts a large following. In a notable scene, Ezekiel, now a preacher, rides into town on a donkey where hordes of people celebrate and welcome his arrival. Vidor’s allusion to Jesus through a Black man is unprecedented. Ezekiel momentarily changes his ways settling down and accepting God’s glory, but when Chick, who has been touched by his words and verbose, is reborn and reenters his life, all those old emotions and human temptations rises up again in Ezekiel making redemption difficult.

Photo courtesy of “Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies”

Chick may be Hallelujah’s side character, but McKinney in undoubtedly the film’s breakout star. Her likable persona bursts through the screen exuding a confident strength brimming in sensuality. Vidor’s admiring gaze fell on the then 16-year-old McKinney during her stint on Broadway in a performance of Blackbirds 1928. Vidor recounts in an interview with Frank Manchel that when scouting New York shows for black talent he spotted her “third from the right in the chorus” and though she was only a background dancer she left a major impression on Vidor (McAlister, 317). He allowed her talent to shine throughout the film granting her moments of exuberant expression and dramatic flair showcasing her ability to simultaneously titillate and break hearts during her numerous crying scenes.

Unfortunately for McKinney her career quickly fizzled just as she appeared to be glowing bright. McKinney’s performance as Chick resulted in a five-year contract with MGM studios, but the studios soon reneged on their promise of finding her work delegating her roles to bit, stereotypical parts. McKinney soon after left Hollywood for Europe finding success as a cabaret performer and stage actress. She made waves as the first black woman to appear on British television with her own special on the BBC along with a slew of other performances and appearances throughout 1936 and 1937.

McKinney returned to American in 1938 starring in a handful of “Race” films. She tried returning to Hollywood in the 1940s as well. Vidor once commented on her by saying “she was so damn beautiful and attractive. The eyes, and everything. She could have had a career, an important career” (Manchel 316). Though Vidor’s starry-eyed hopes were high for McKinney, reality proved otherwise and Hollywood reduced her talent to bit, stereotypical roles throughout the Studio Era of the 1940s. McKinney left America after WWII living in Athens, Greece before returning to New York where she died in 1967 of a heart attack.

Despite Vidor’s sincere intentions to produce an almost docudrama of Southern black life as a way of showcasing his deep love and admiration for the songs he heard and the people he knew growing up, Hallelujah was only a minor success. Racial mindsets of the time prevented the film from showing in the South and the North had only few showings in major cities, many if not all of those showings segregated. Even today Hallelujah may not sit well with audiences across the board.

However, I think it’s important to uphold the legacy of this film even if its images weren’t as forward thinking as one would wish. Hallelujah was ahead of its time. McKinney often gets trivialized in negative reviews of the film for embodying the “Tragic Mulatto” stereotype in Hollywood’s portrayal of Black characters, as well as setting the standard for lighter skinned women to lead films. Considering McKinney’s strong role and self-assurance throughout Hallelujah, I’d argue that this typecast has no bearings on McKinney.

I’d also argue that the darker skinned Spivey’s role in the film rivals that of McKinney’s in both screen time and substance as Spivey gets to emit emotional complexity in an outstanding performance. Spivey endured longevity in her career through musical films and stage shows. Spivey’s musical career kept her afloat after the Great Depression and she went on make an impression in the Folk music scene of the 1960s and even initiated her own record label in 1963.

Hallelujah highlights the cultural standards of Southern black life at the time and makes a point of giving African-American’s their time to shine, even forgoing elements of reality by not including a single white face or hand throughout the film. The characters of the film experience multifaceted situations and a range of emotions all the while expressing the role of God in making hard times bearable through song and dance. It’s important that we look at Hallelujah for what it was due to the time, era, and studio it came from and not hold it to unrealistic standards. To do so diminishes the worth of the hundreds of black extras that were hired, the black actors who had starring roles, and the two leads who’s biggest most complex roles were the characters they played.

Additional Citations:

Manchel, Frank (2007). Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies. New Academia Publishing.

McAlister, Elizabeth and Henry Goldschmidt (2004). Race, Nation, and Religion in the Americas. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Richards, Larry (1998). African American Films Through 1959. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

America has a race problem. Only when we can truly understand and admit this simple fact is when this country can grow past its tainted history and progress into the post-racial society so many of us like to pretend we live in. The conscious awareness centering on the immutable achievements from members of the African diaspora needs expansion. This awareness of the power and talents within members of the African diaspora all around the world is needed to enlighten the populace, thereby diminishing the permeating air of white supremacy dominating the mindset in many developed countries today. Even film, the birthplace of imagination, has lacked the fortitude to spread the stories and faces of people of color to the masses in order to highlight their achievements.

The focus during Black History Month has too often been nothing more than attempts, whether intentional or not, to remind the African diaspora that slavery is the biggest part of our history. Undoubtedly for African Americans this fact is a dire, undesired truth, as half of our 400 years in this country was spent in large part in servitude. But, our focus instead should be on the powerful, unscrupulous achievements made by a group of people whose own country had little faith in them and attempted to constantly keep them at a disadvantage.

Two years ago, I did a retrospective on the history chronicling African American filmmakers. That retrospective focused inadvertently on males. This year I want to highlight and praise the works of female filmmakers, not just African American, but from all over the world in the African Diaspora. Most of these pioneering women who I will focus on weren’t even known to me two years when researching the role of African Americans in early filmmaking. What I’ve come to discover is that black women have played a lively role in early filmmaking from the 1910’s into 1930’s. Unfortunately, due to a lack of care and support many of these women’s names have faded into obscurity and prints of their films are hard to come by, if they have resurfaced.

Two names that have stood the test of ages for African American female filmmakers is Maria P. Williams and Tressie Sounders. Repeat and remember these names. Sounders is credited as the writer, director, and producer of the 1922 film A Woman’s Error. The film, distributed by the Afro-American Film Exhibitors Company in Kansas, City, Missouri received glowing reviews from The Billboard during its release. The Billboard considered the film a “picture true to the Negro life” and saw it as “the first of its kind to be produced by a young woman of our race” (Morgan).

It is not known how Sounders, a Frankfort, Kentucky native and maid by trade, found herself directing a feature-length film, but speculation falls on the movement of filmmaking that took place in metropolitan areas throughout the Midwest from about 1916 into the 1920s. The Afro-American Film Exhibitors Company contacted Sounders expressing their wish to distribute her film. A year later, another trailblazer went on to put her stamp in the film world. Maria P. Williams became officially touted as the “first colored woman producer in the United States” by the Norfolk Journal & Guide in 1923. Williams’ five reel mystery drama Flames of Wrath had the proud title of being completely “written, acted and produced entirely by colored people.”

Williams’ career initially focused on social activism and leadership. Similar to film pioneer Oscar Micheaux, Williams wrote a short autobiography of her life titled My Work and Public Sentiment in 1916. Williams’ induction into the film world flowed much easier than Sounders’ due in part to Williams’ husband, Jesse L. Williams who served as president of The Western Film Producing Company and Booking Exchange where Maria acted as a treasurer and secretary. Maria also worked as an assistant manager at the motion picture theater where her husband operated as general manager (Morgan). In 1923, Williams released Flames of Wrath producing much chatter among film distributors and theater managers along with it.

The film is summarized as a mystery drama following the exploits of an escaped prisoner and the diamond ring he buries before his jail sentencing. The ring becomes the centerpiece of drama as a young boy finds it and gives it to his older brother while a vindictive lawyer plots to steal it away. The lawyer’s assistant, Pauline Keith, learns of the conspiracy and investigates. Through her work she later saves the innocent brother from the lawyer’s shady plans (Gevinson, 338).

An intriguing aspect that should be noted here is the Norfolk Journal & Guide’s coverage of Flames of Wrath. The credits state that the film is “headed by: Roxie Mankins and John Burton.” Throughout the history of Williams’ association with Flames of Wrath she has been presented as the film’s producer. Roxie, an African American actress who starred in the film as Pauline Keith, “heads” the film which may have been silent film lingo indicating her directorial association.

Flames of Wrath endured a lengthy distribution circuit around the country as noted in Roger Wilson’s letter to the manager of the Douglas Theater in Macon, Georgia, the city’s biggest colored theater at the time. On September 8, 1925, Wilson, Manager for State of Tarpon Springs, Florida, wrote an inquiry for the Douglas Theater to rent the five reel picture at a cost of $25 a day. Wilson boasted his confidence in the picture claiming it had “never lost a dollar to an exhibitor in all of its rounds.”

Kansas City, Missouri became a hot bed of activity and growth for African Americans who moved their seeking refuge at the turn of the century. An often ignored aspect that affected the African American community and the country as whole even today is “The Great Migration” as it became known. This exciting time for many African Americans in the United States presented a large percentage of black families with a choice: either stay in the South and endure the growing negation of Jim Crow Laws and the unlivable conditions that mounting racism presented or take a chance on new opportunities in the North. This “Exoduster” became such a widespread, sensationalized event that the 1880 Senate committee was appointed to investigate it.

The industries of the North expanded during and after World War I welcoming new labor into bustling cities of the North and Midwest like Chicago, Kansas City, Cleveland, New York, and Detroit among other cities. In the fall and winter of 1916-1917, the earlier months of The Great Migration, recruiters working for Northern industry would often attract Southerners with stories of high wages and better living conditions in the North. These recruiters were often given cash incentives to recruit reliable friends and relatives, a task that proved all too easy due to the reputation of the lavish lives and bountiful opportunities in the North. James R. Grossman recounts how Blues musician Tampa Red remembered Pullman car porters traveling through Florida describing Chicago to Southerners as “God’s country” (Grossman, 106).

It’s no wonder how Tressie Sounders, a Kentucky native, found her way into the filmmaking business when she reached Kansas City. Likewise, another black female that made a living within the motion picture buisness after a migration from Texas to Washington D. C. was Eloyce King Patrick Gist. Along with her husband James Gist, Eloyce produced silent films with a spiritual bend. Eloyce is believed to have re-written and re-edited the 16mm print of her husband’s film Hell Bound Train in 1929. By the early 1930’s, Eloyce and James worked together on their 7-minute film Verdict Not Guilty.

Though Eloyce was of Bahá’í faith and her husband was a self-ordained Christian evangelical preacher both enjoyed delivering their spiritual messages in African American community groups and churches. The couple toured the country with their films making spectacles of their screenings. Eloyce would play piano and lead the congregation in hymns, followed by the screening of the film, then a quick sermon by James. The NAACP picked up on the group’s efforts announcing its support in 1933. The surviving prints of Hell Bound Train that have been reassembled and digitized were reportedly in shreds due to the popularity and multiple showings of the film during its time in the light (Black Film Reel pg. 20).

Throughout the 1920’s black women like Alice B. Russell and Eslanda Robeson found themselves in front of the lens of a camera. Even still, many black women continued to helm visual cues from behind the lens of a camera. The legendary Zora Neale Hurston who would later break color barriers in 1937 with her famed novel Their Eyes Were Watching God showcased her love for real life narrative through her work behind the camera. Hurston moved to Harlem from Washington D.C. with only an Associate’s degree from Howard University. Hurston’s bright personality fit well in the hustle and bustle of New York and soon she caught the eye of American author Annie Nathan Meyer who offered Hurston a scholarship to Barnard College. Under the tutelage of anthropologist Franz Boas, Hurston took up anthropology becoming the first black person to graduate from the institution.

Afterwards, Hurston spent about two years studying the customs, folklore, work songs, and spirituals of the rural south while traveling from New Orleans to Florida. Reportedly, with a handgun, a two dollar dress, and a 16mm camera packed with her, Hurston documented the life of Cudjo “Kossula” Lewis, whom she believed to be the sole remaining survivor of the Clotilde, the last arriving slave ship to the United States (in 1859). She also documented workers for the Everglades Cypress Lumber Company, and a river baptism cementing her status as one of the many black female directors of silent cinema.

Across the board, members of the African diaspora have done more than become a mere lot of firsts in a rigged game where whites have already hit the finish line. Our history is colored with not just firsts, but movements of change and progress despite being handicapped by a system of racism that pitted African Americans out of ideal situations based on the color of their skins. Black History Month is often a time when the highlights of our history is minimized to the perils that the black race in America have endured. But as this research shows, our legacy has been both exceptional and mundane in the grand scheme of American history. These women simply did what they desired to do and that was make movies when they had the opportunity to do so.

Too often do we reduce the glory of African Americans who have always persevered and achieved despite the disadvantages they were given. History tends to ignore past filmmakers who joined the ranks of motion picture making, a tactic that negatively installs in the heads of many that African Americans haven’t achieved much in our time within this country. When the research is done, the opposite of that assumption proves to reign supreme. African Americans have built their own self-reliant towns, been millionaires (e.g. “Black Wall Street”) , lived peacefully, lived mundanely, and wrote, directed, produced and starred in their own films that represent life from their reality. But, time and again these relics have been destroyed and forgotten by the racist systems currently in place that wish to suppress the deeds of minorities.

2016 will be a year of progress and further advancement for and by African Americans and the first step to advancing the achievements of African Americans is to recognize them. This year will see a cascade of work from members of the African diaspora. The Sundance Film Festival is currently riding a wave of excitement about films by black creators. Fox Searchlight even made a historic bid of $17.5 million that bought writer and director Nate Parker’s story of the famed slave revolter Nat Turner in Birth of a Nation for distribution. Director Ava DuVernay is in talks of being both the first African American and first female director of a Marvel superhero film.

The pendulum of progress has been swinging at an excruciatingly slow pace throughout our generations. To give it that extra push it needs, it is important that we all take the individual effort to support these films, new and old, and embrace the stories they tell. I’m not asking anyone to feign an appreciation for a film they don’t like, but I am requesting that we give these films and their directors the chance that the Academy themselves seem intent on ignoring until outcry takes place.

Additional Citations:

Morgan, Kyna. “Tressie Souders.” In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. Web. September 27, 2013.

Morgan, Kyna. “Maria P. Williams.” In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. Web. September 27, 2013. <https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pioneer/maria-p-williams-2/>

Gevinson, Alan. Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911-1960 pp. 338

Wilkerson, Isable. Interview, NPR September 13, 2010.

Grossman, James R. A Chance to Make Good. Oxford University Press, 1997.

-large-picture.jpg)