A Spotlight on Female African American Filmmakers of Early Cinema (1916-1928)

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

America has a race problem. Only when we can truly understand and admit this simple fact is when this country can grow past its tainted history and progress into the post-racial society so many of us like to pretend we live in. The conscious awareness centering on the immutable achievements from members of the African diaspora needs expansion. This awareness of the power and talents within members of the African diaspora all around the world is needed to enlighten the populace, thereby diminishing the permeating air of white supremacy dominating the mindset in many developed countries today. Even film, the birthplace of imagination, has lacked the fortitude to spread the stories and faces of people of color to the masses in order to highlight their achievements.

The focus during Black History Month has too often been nothing more than attempts, whether intentional or not, to remind the African diaspora that slavery is the biggest part of our history. Undoubtedly for African Americans this fact is a dire, undesired truth, as half of our 400 years in this country was spent in large part in servitude. But, our focus instead should be on the powerful, unscrupulous achievements made by a group of people whose own country had little faith in them and attempted to constantly keep them at a disadvantage.

Two years ago, I did a retrospective on the history chronicling African American filmmakers. That retrospective focused inadvertently on males. This year I want to highlight and praise the works of female filmmakers, not just African American, but from all over the world in the African Diaspora. Most of these pioneering women who I will focus on weren’t even known to me two years when researching the role of African Americans in early filmmaking. What I’ve come to discover is that black women have played a lively role in early filmmaking from the 1910’s into 1930’s. Unfortunately, due to a lack of care and support many of these women’s names have faded into obscurity and prints of their films are hard to come by, if they have resurfaced.

Two names that have stood the test of ages for African American female filmmakers is Maria P. Williams and Tressie Sounders. Repeat and remember these names. Sounders is credited as the writer, director, and producer of the 1922 film A Woman’s Error. The film, distributed by the Afro-American Film Exhibitors Company in Kansas, City, Missouri received glowing reviews from The Billboard during its release. The Billboard considered the film a “picture true to the Negro life” and saw it as “the first of its kind to be produced by a young woman of our race” (Morgan).

It is not known how Sounders, a Frankfort, Kentucky native and maid by trade, found herself directing a feature-length film, but speculation falls on the movement of filmmaking that took place in metropolitan areas throughout the Midwest from about 1916 into the 1920s. The Afro-American Film Exhibitors Company contacted Sounders expressing their wish to distribute her film. A year later, another trailblazer went on to put her stamp in the film world. Maria P. Williams became officially touted as the “first colored woman producer in the United States” by the Norfolk Journal & Guide in 1923. Williams’ five reel mystery drama Flames of Wrath had the proud title of being completely “written, acted and produced entirely by colored people.”

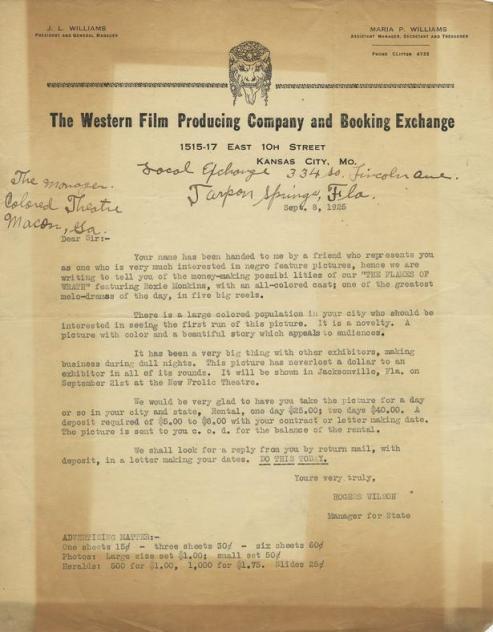

Williams’ career initially focused on social activism and leadership. Similar to film pioneer Oscar Micheaux, Williams wrote a short autobiography of her life titled My Work and Public Sentiment in 1916. Williams’ induction into the film world flowed much easier than Sounders’ due in part to Williams’ husband, Jesse L. Williams who served as president of The Western Film Producing Company and Booking Exchange where Maria acted as a treasurer and secretary. Maria also worked as an assistant manager at the motion picture theater where her husband operated as general manager (Morgan). In 1923, Williams released Flames of Wrath producing much chatter among film distributors and theater managers along with it.

The film is summarized as a mystery drama following the exploits of an escaped prisoner and the diamond ring he buries before his jail sentencing. The ring becomes the centerpiece of drama as a young boy finds it and gives it to his older brother while a vindictive lawyer plots to steal it away. The lawyer’s assistant, Pauline Keith, learns of the conspiracy and investigates. Through her work she later saves the innocent brother from the lawyer’s shady plans (Gevinson, 338).

An intriguing aspect that should be noted here is the Norfolk Journal & Guide’s coverage of Flames of Wrath. The credits state that the film is “headed by: Roxie Mankins and John Burton.” Throughout the history of Williams’ association with Flames of Wrath she has been presented as the film’s producer. Roxie, an African American actress who starred in the film as Pauline Keith, “heads” the film which may have been silent film lingo indicating her directorial association.

Flames of Wrath endured a lengthy distribution circuit around the country as noted in Roger Wilson’s letter to the manager of the Douglas Theater in Macon, Georgia, the city’s biggest colored theater at the time. On September 8, 1925, Wilson, Manager for State of Tarpon Springs, Florida, wrote an inquiry for the Douglas Theater to rent the five reel picture at a cost of $25 a day. Wilson boasted his confidence in the picture claiming it had “never lost a dollar to an exhibitor in all of its rounds.”

Kansas City, Missouri became a hot bed of activity and growth for African Americans who moved their seeking refuge at the turn of the century. An often ignored aspect that affected the African American community and the country as whole even today is “The Great Migration” as it became known. This exciting time for many African Americans in the United States presented a large percentage of black families with a choice: either stay in the South and endure the growing negation of Jim Crow Laws and the unlivable conditions that mounting racism presented or take a chance on new opportunities in the North. This “Exoduster” became such a widespread, sensationalized event that the 1880 Senate committee was appointed to investigate it.

The industries of the North expanded during and after World War I welcoming new labor into bustling cities of the North and Midwest like Chicago, Kansas City, Cleveland, New York, and Detroit among other cities. In the fall and winter of 1916-1917, the earlier months of The Great Migration, recruiters working for Northern industry would often attract Southerners with stories of high wages and better living conditions in the North. These recruiters were often given cash incentives to recruit reliable friends and relatives, a task that proved all too easy due to the reputation of the lavish lives and bountiful opportunities in the North. James R. Grossman recounts how Blues musician Tampa Red remembered Pullman car porters traveling through Florida describing Chicago to Southerners as “God’s country” (Grossman, 106).

It’s no wonder how Tressie Sounders, a Kentucky native, found her way into the filmmaking business when she reached Kansas City. Likewise, another black female that made a living within the motion picture buisness after a migration from Texas to Washington D. C. was Eloyce King Patrick Gist. Along with her husband James Gist, Eloyce produced silent films with a spiritual bend. Eloyce is believed to have re-written and re-edited the 16mm print of her husband’s film Hell Bound Train in 1929. By the early 1930’s, Eloyce and James worked together on their 7-minute film Verdict Not Guilty.

Though Eloyce was of Bahá’í faith and her husband was a self-ordained Christian evangelical preacher both enjoyed delivering their spiritual messages in African American community groups and churches. The couple toured the country with their films making spectacles of their screenings. Eloyce would play piano and lead the congregation in hymns, followed by the screening of the film, then a quick sermon by James. The NAACP picked up on the group’s efforts announcing its support in 1933. The surviving prints of Hell Bound Train that have been reassembled and digitized were reportedly in shreds due to the popularity and multiple showings of the film during its time in the light (Black Film Reel pg. 20).

Throughout the 1920’s black women like Alice B. Russell and Eslanda Robeson found themselves in front of the lens of a camera. Even still, many black women continued to helm visual cues from behind the lens of a camera. The legendary Zora Neale Hurston who would later break color barriers in 1937 with her famed novel Their Eyes Were Watching God showcased her love for real life narrative through her work behind the camera. Hurston moved to Harlem from Washington D.C. with only an Associate’s degree from Howard University. Hurston’s bright personality fit well in the hustle and bustle of New York and soon she caught the eye of American author Annie Nathan Meyer who offered Hurston a scholarship to Barnard College. Under the tutelage of anthropologist Franz Boas, Hurston took up anthropology becoming the first black person to graduate from the institution.

Afterwards, Hurston spent about two years studying the customs, folklore, work songs, and spirituals of the rural south while traveling from New Orleans to Florida. Reportedly, with a handgun, a two dollar dress, and a 16mm camera packed with her, Hurston documented the life of Cudjo “Kossula” Lewis, whom she believed to be the sole remaining survivor of the Clotilde, the last arriving slave ship to the United States (in 1859). She also documented workers for the Everglades Cypress Lumber Company, and a river baptism cementing her status as one of the many black female directors of silent cinema.

Across the board, members of the African diaspora have done more than become a mere lot of firsts in a rigged game where whites have already hit the finish line. Our history is colored with not just firsts, but movements of change and progress despite being handicapped by a system of racism that pitted African Americans out of ideal situations based on the color of their skins. Black History Month is often a time when the highlights of our history is minimized to the perils that the black race in America have endured. But as this research shows, our legacy has been both exceptional and mundane in the grand scheme of American history. These women simply did what they desired to do and that was make movies when they had the opportunity to do so.

Too often do we reduce the glory of African Americans who have always persevered and achieved despite the disadvantages they were given. History tends to ignore past filmmakers who joined the ranks of motion picture making, a tactic that negatively installs in the heads of many that African Americans haven’t achieved much in our time within this country. When the research is done, the opposite of that assumption proves to reign supreme. African Americans have built their own self-reliant towns, been millionaires (e.g. “Black Wall Street”) , lived peacefully, lived mundanely, and wrote, directed, produced and starred in their own films that represent life from their reality. But, time and again these relics have been destroyed and forgotten by the racist systems currently in place that wish to suppress the deeds of minorities.

2016 will be a year of progress and further advancement for and by African Americans and the first step to advancing the achievements of African Americans is to recognize them. This year will see a cascade of work from members of the African diaspora. The Sundance Film Festival is currently riding a wave of excitement about films by black creators. Fox Searchlight even made a historic bid of $17.5 million that bought writer and director Nate Parker’s story of the famed slave revolter Nat Turner in Birth of a Nation for distribution. Director Ava DuVernay is in talks of being both the first African American and first female director of a Marvel superhero film.

The pendulum of progress has been swinging at an excruciatingly slow pace throughout our generations. To give it that extra push it needs, it is important that we all take the individual effort to support these films, new and old, and embrace the stories they tell. I’m not asking anyone to feign an appreciation for a film they don’t like, but I am requesting that we give these films and their directors the chance that the Academy themselves seem intent on ignoring until outcry takes place.

Additional Citations:

Morgan, Kyna. “Tressie Souders.” In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. Web. September 27, 2013.

Morgan, Kyna. “Maria P. Williams.” In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. Center for Digital Research and Scholarship. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2013. Web. September 27, 2013. <https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pioneer/maria-p-williams-2/>

Gevinson, Alan. Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911-1960 pp. 338

Wilkerson, Isable. Interview, NPR September 13, 2010.

Grossman, James R. A Chance to Make Good. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Thanks so much for this article, Quatoyiah, and for quoting my work with the Women Film Pioneers Project at Columbia University! It’s so important for people to keep pushing forward with this kind of research. Like I’ve said before, the list of people needing to be written back into history is a very long one! It’s only through consistent writing, sharing, and furthering of our research that groups and individuals needing to have their voices and work reasserted will be recognized and studied more broadly. This is how we will make a change. Thanks again!