Hallelujah (1929); And the Highlight of African-American Actresses in Early Hollywood

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

For part 1 of this ongoing series, begin here.

By 1929, dozens of films starring African-Americans that centered on their stories illuminated the screens of theaters throughout the country. Most were shorts, musicals, questionably racist ethnography films, and features from all-Black production studios. Sadly, based on current knowledge, not a single film from this period was produced or helmed by Black women. Hollywood soon decided to try its chance at dipping into the production of “Race” films. These were films aimed at attracting larger groups of minorities through all-inclusive casts of African-Americans and Chinese-Americans. Hollywood studios made two films that year, Hearts in Dixie and Hallelujah. Although these films were white productions, Hallelujah was the only to present Nina Mae McKinney to the world, Hollywood’s first Black actress, while also featuring Blues singer and songwriter Victoria Spivey as the film’s supporting actress.

Many of the films featured in 1929 are deemed lost rendering it impossible for contemporary viewers to see them. My focus will tighten largely on Hallelujah, the most famous of that year and most accessible to watch. Hallelujah shamelessly promotes the beauty and talents of African-American women when other films in Hollywood couldn’t even conceive the thought to do so. At the heart of Hallelujah’s story are the joys and sorrows of a Black Southern family and its oldest son Ezekiel (Daniel L. Haynes).

Hallelujah was met with mixed reviews for its portrayal of African-Americas during its release to the public. The same mixed feelings then has and will continue to permeate contemporary audiences today. But, despite its controversial portrayals, I think it’s important to stay open-minded when viewing Hallelujah and to see it as a relic of its time that possesses great importance like none before it.

Hallelujah and Hearts in Dixie distinguished themselves through two important attributes. Released just months apart, both were Hollywood’s first “all-Black” casted films as well as some of the earliest “Talkies” when Hollywood transitioned over from silent films into sound. Mutually, these films were directed by white men with careers already established in Hollywood. Nevertheless, both heralds notable achievements setting them apart from the rest of Hollywood’s films at the time.

King Vidor’s Hallelujah was a conscious attempt by the director to create a film that accurately portrayed the Southern black family. Vidor enlisted the help of Hollywood’s only female screenwriter at the time, Wanda Tuchock, to assist with the screenplay and casted the talented Nina Mae McKinney as Hallelujah’s lead. The male exclusive production of Hearts in Dixie doesn’t bar it from its own personal acme. Larry Richards’ African American Films Through 1959 lists the film’s staring actor, Clarence Muse, as having aided in the direction of the film, an uncommon aspect in Hollywood in 1929.

The first twenty minutes or so of Hallelujah is very hard to swallow. A Southerner by birth, Vidor’s earnest intentions were to produce a film that showed African-Americans as fair and true to life as he could. Vidor’s idea for Hallelujah bore from a secret hope he held for years of producing an all-Black casted film about Southern life. His idea got turned down by studios every time he mentioned it. Once sound hit Hollywood in 1927 with The Jazz Singer, Vidor seized the opportunity to make his dream film a reality. He so strongly believed in his concept that when studio executives feared the lack of revenue for not attracting enough white audience members, Vidor offered to forgo his own salary to make the film. The studio reluctantly allowed him to make Hallelujah.

But, while some reviewers praised the film after its release others condemned it. As one New York reviewer said of the film to Amsterdam News:

“After the picture was well under way on its opening night, it was clearly to be seen that the superb acting of the cast was being over shadowed by the amount of spirituals, meaning the weeping and wailing and the weak, the love [in] spirit were dominating the picture. When one sees “Hallelujah,” stripped to the bone and laid bare it is not hard to imagine why Harlem is the largest Negro City in America, why Chicago, Philadelphia, and Baltimore and the others are increasing in Negro populations. “Hallelujah” is the answer.” (McAlister, 321)

At first glance, Hallelujah seems to uphold all those old stereotypes of African-Americans which is bittering and indignant to witness. We watch as Black bodies line the cotton fields of Memphis, Tennessee picking cotton and singing out spirituals and hymns with an unbelievable joy and sprite that doesn’t fully reflect the plight endured by those who may have been born into slavery, freed by the Emancipation, and had to resort back to cotton picking because rampant racism and segregation left day labor jobs available to primarily African-Americans.

Once we leave the cotton fields Vidor invites audiences into the homes of the African-American family we are following. They sit for a meal of chitilins and spare ribs and their oldest son, Ezekiel (Haynes), brings out a banjo while the family engages in an after dinner jig with the youngest of the family tap dancing on tables as they all sing together. Now right here, it was very hard for me to continue watching. My annoyance at these portrayals grew as I expected to hear the demeaning words “yes massa” and “I sholl do love pickin cotton” along with other horribly racist images and vernacular that was all too present in the time period. These caricatures have gotten singed into the general consciousness of society for decades. So much so that many of us are actually ashamed to eat fried chicken in public and even utter the word “watermelon”.

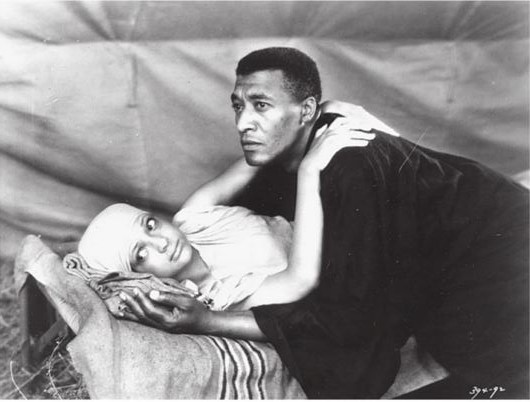

Photo courtesy of “Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies”

But, Vidor doesn’t allow Hallelujah to live up to these expectations though it certainly seems to flirt with it. A white man who grew up with an African-American matriarch in his home, Vidor admitted in an interview that he wanted to dedicate the film to the woman who was more of a mother to him than his own (Manchel, 330). Though his portrayals are cringe worthy they speak of the time period in which Vidor grew. At 34 years old he made Hallelujah based off the experiences he had in adolescence. In that 30 year period a world of change developed quickly for the Northern half of the country due to Reconstruction and The Great Migration.

These moments of cringe worthy portrayals exist throughout the film due to the melodrama of the film itself, but they stop feeling like caricatures and start developing into what they were intended to be; representations of life in the South overdramatized by music in an era when sound boomed in Hollywood. We watch as Fanny Belle de Knight, the film’s matriarch, rocks her children to sleep with a sweet, soul-satisfying lullaby given us a homely view of these people’s lives. There’s humor within this family as they joke and pick on one another and they celebrate the union of neighbors with a wedding song and dancing.

A scene in particular that caused me to squirm in discomfort came when Ezekiel irrepressibly forces a kiss on Ms. Rose (Spivey), his house mate who he’s attracted to. Immediately this scenes conjures up the stereotype of the “Black Buck,” a male unable to control himself usually at the sight of a lily-white woman. Yet, again Vidor crushes these expectations by making the object of his desire a Black woman and immediately Ezekiel regrets his impassioned actions and apologizes to Rose. This scene becomes an indication of things to come and a look into Ezekiel’s individual personality as opposed to a stereotype on all black men. This act of passion is foreshadowing for the situations that happens to Ezekiel later finds himself from not being able to control his emotions.

Photo courtesy of “Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies”

Zeke’s hard work ultimately grants him pay of $100, a sizable amount of money that he takes to a local club to celebrate with. This is the scene where the representation of African-Americans expands shifting the focus and that unsettling feeling I initially had throughout the start of the film. Here we see a host of dapper, well off African-Americans listening and dancing to Jazz music and finally we meet Chick (McKinney), a “Femme Fatale” of great beauty and a bubbling personality. Vidor has no shame in focusing on the beauty of McKinney through close-ups of her face, legs, and keeping her centered in the action.

From here the story follows a row Ezekiel has at the club when he gets swindled of his money. His inability to control his emotions causes him to shoot a character and painful regret he endures turns him into a man of God. Ezekiel’s search for divinity and forgiveness for his actions triggers impassioned sermons that attracts a large following. In a notable scene, Ezekiel, now a preacher, rides into town on a donkey where hordes of people celebrate and welcome his arrival. Vidor’s allusion to Jesus through a Black man is unprecedented. Ezekiel momentarily changes his ways settling down and accepting God’s glory, but when Chick, who has been touched by his words and verbose, is reborn and reenters his life, all those old emotions and human temptations rises up again in Ezekiel making redemption difficult.

Photo courtesy of “Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies”

Chick may be Hallelujah’s side character, but McKinney in undoubtedly the film’s breakout star. Her likable persona bursts through the screen exuding a confident strength brimming in sensuality. Vidor’s admiring gaze fell on the then 16-year-old McKinney during her stint on Broadway in a performance of Blackbirds 1928. Vidor recounts in an interview with Frank Manchel that when scouting New York shows for black talent he spotted her “third from the right in the chorus” and though she was only a background dancer she left a major impression on Vidor (McAlister, 317). He allowed her talent to shine throughout the film granting her moments of exuberant expression and dramatic flair showcasing her ability to simultaneously titillate and break hearts during her numerous crying scenes.

Unfortunately for McKinney her career quickly fizzled just as she appeared to be glowing bright. McKinney’s performance as Chick resulted in a five-year contract with MGM studios, but the studios soon reneged on their promise of finding her work delegating her roles to bit, stereotypical parts. McKinney soon after left Hollywood for Europe finding success as a cabaret performer and stage actress. She made waves as the first black woman to appear on British television with her own special on the BBC along with a slew of other performances and appearances throughout 1936 and 1937.

McKinney returned to American in 1938 starring in a handful of “Race” films. She tried returning to Hollywood in the 1940s as well. Vidor once commented on her by saying “she was so damn beautiful and attractive. The eyes, and everything. She could have had a career, an important career” (Manchel 316). Though Vidor’s starry-eyed hopes were high for McKinney, reality proved otherwise and Hollywood reduced her talent to bit, stereotypical roles throughout the Studio Era of the 1940s. McKinney left America after WWII living in Athens, Greece before returning to New York where she died in 1967 of a heart attack.

Despite Vidor’s sincere intentions to produce an almost docudrama of Southern black life as a way of showcasing his deep love and admiration for the songs he heard and the people he knew growing up, Hallelujah was only a minor success. Racial mindsets of the time prevented the film from showing in the South and the North had only few showings in major cities, many if not all of those showings segregated. Even today Hallelujah may not sit well with audiences across the board.

However, I think it’s important to uphold the legacy of this film even if its images weren’t as forward thinking as one would wish. Hallelujah was ahead of its time. McKinney often gets trivialized in negative reviews of the film for embodying the “Tragic Mulatto” stereotype in Hollywood’s portrayal of Black characters, as well as setting the standard for lighter skinned women to lead films. Considering McKinney’s strong role and self-assurance throughout Hallelujah, I’d argue that this typecast has no bearings on McKinney.

I’d also argue that the darker skinned Spivey’s role in the film rivals that of McKinney’s in both screen time and substance as Spivey gets to emit emotional complexity in an outstanding performance. Spivey endured longevity in her career through musical films and stage shows. Spivey’s musical career kept her afloat after the Great Depression and she went on make an impression in the Folk music scene of the 1960s and even initiated her own record label in 1963.

Hallelujah highlights the cultural standards of Southern black life at the time and makes a point of giving African-American’s their time to shine, even forgoing elements of reality by not including a single white face or hand throughout the film. The characters of the film experience multifaceted situations and a range of emotions all the while expressing the role of God in making hard times bearable through song and dance. It’s important that we look at Hallelujah for what it was due to the time, era, and studio it came from and not hold it to unrealistic standards. To do so diminishes the worth of the hundreds of black extras that were hired, the black actors who had starring roles, and the two leads who’s biggest most complex roles were the characters they played.

Additional Citations:

Manchel, Frank (2007). Every Step a Struggle: Interviews with Seven who Shaped the African-American Image in Movies. New Academia Publishing.

McAlister, Elizabeth and Henry Goldschmidt (2004). Race, Nation, and Religion in the Americas. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Richards, Larry (1998). African American Films Through 1959. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.

-large-picture.jpg)

Trackbacks